Fraser can claim the title of the Fittest Man on Earth, having won the men’s division of the CrossFit Games for the past three years in a row. The event began in 2007, according to the website, “to fill a void. From Ironman triathlons to the NFL, all other athletic events neglected to accurately test fitness.” Sure, you might be able to swim 3.8km, cycle 180km, then run a marathon. But how many muscle-ups can you do?

Broadcast on US network CBS Sport and beamed around the world on Facebook, the Games are the Super Bowl of CrossFit, “the sport of fitness” that comprises elements of strength, conditioning, Olympic weightlifting and gymnastics. One of this century’s defining fitness trends, CrossFit engineered a shift from static gym equipment such as pec decks and leg-extension machines to utilitarian rigs, ropes and sleds. It prescribes “varied, high-intensity, functional movements” – particularly “moving large loads, long distances, quickly”. It was founded in 2000 by Greg Glassman, who as a teenage gymnast discovered that lifting weights and cycling made him a better all-round athlete than his single-discipline peers.

It has since spread across the globe thanks to its cultish sense of community and the fact that it is undeniably effective. Perhaps the key ingredient of its secret sauce, however, is its measurability: anybody from the fit to the infirm can complete the Workout of the Day in one of the 15,000-plus “boxes” (CrossFit for gym) worldwide and see how they compare.

RELATED: This Is What The ‘Fittest Man On Earth’ Eats… Before Smoking The Competition

“I have no perception of what it would be like to play basketball against LeBron James,” says Fraser. “The thought of someone that big who can move the way he does, it’s unfathomable. I watch him and appreciate him but, if I faced him, I’d have a whole new appreciation. I’m sure 99% of people who watch someone do a snatch are, like, ‘OK, whatever.’ Go grab a barbell and try to do one. Now you can compare.”

The climax of the CrossFit season, the Games are a series of demanding events unknown to the athletes until moments before they hear, “Three, two, one, go!” For example, the male qualifiers (there are also women’s, masters’, teenagers’ and team categories) might have to cycle 10 laps of a 1,200m track, perform 30 muscle-ups, row a marathon (42.2km) or squat, shoulder press and deadlift a one-rep max. In fact, they did all of that on day one of the 2018 Games, which then went on for another four days. (Although the second was a rest day…)

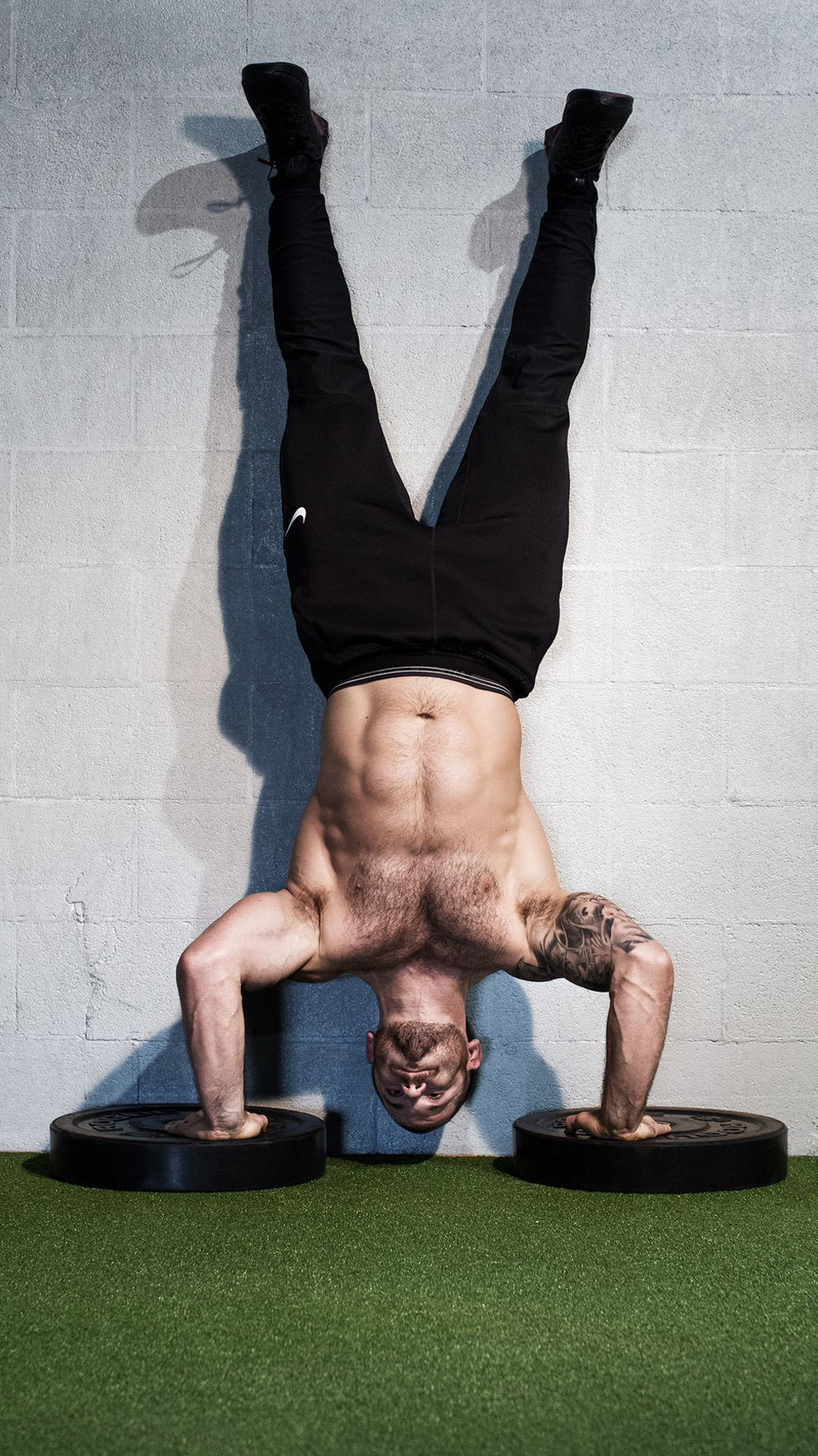

Each event awards first place 100 points, second place 99, and so on. To win the CrossFit Games with a record 1,162 points out of a possible 1,400 and claim the USD $300,000 prize money, as Fraser did in 2018, you have to be good at a lot of different things. Fraser finished fourth or better in 10 of the 14 events, and first in two: the Fibonacci – five, eight, then 13 reps each of handstand press-ups and deadlifts with two 92kg kettlebells, followed by 27m of lunges, holding 24kg kettlebells overhead – and the Aeneas – five pegboard climbs, 40 thrusters (a squat and overhead press with 38kg) and three 10m walks carrying a yoke (a kind of squat rack-cum-sled), loaded with 193kg, 256kg, then 302kg. In both cases, he’d already completed two gruelling events earlier the same day.

Fraser’s record victory margin of 220 points broke his own record of 216 points, set in 2017 (after tearing his lateral collateral ligament in his knee at the end of the first day), which broke the record of 197 that he had set in 2016. In other words, he’s getting better at being better than everybody else. CNN contrasted Fraser’s unrivaled position in the sport of fitness to other disciplines in which rivals spur each other on to greatness: Ronaldo vs Messi, Federer vs Nadal, Ali vs Frazier. In CrossFit, it’s Fraser vs Fraser.

“We don’t even know how good Mat Fraser is,” CrossFit’s then media director said ahead of his 2018 victory. “He should have to run a marathon before the Games to level the playing field.” Ominously, Fraser booked his place at the 2019 Games at the first opportunity by winning the first qualifying round in December, giving him eight months to focus on August’s Games. And, at 29, he’s still in his prime.

Holding Your Nerve

Despite his superiority, Fraser often dry-heaves or even throws up from pre-competition tension. He reminds himself of what is within his control and says a prayer like the one tattooed on his shoulder: “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can and the wisdom to know the difference.”

Sport psychologists talk about the importance of a “growth mindset”: the belief that your attributes aren’t “fixed”, that they can be developed. A three-time junior national weightlifting champion and former US Olympic weightlifting prospect, Fraser has short levers that are advantageous for lifting but less so for, say, rowing, which didn’t come naturally. Helpfully, the box he trained at in Vermont, his home state, was also frequented by employees of nearby rowing machine manufacturer Concept2, one of whom taught him proper technique.

“Extend your legs, extend your hips, then follow through with the arms,” explains Fraser, who rowed up to 5km per day until his weakness became a strength. “It’s an unnatural feeling, but after a million meters, you get the hang of it.” His stroke will never be as long as his competitors’: “But I just use that as a reason to get even better at it.”

Fraser hasn’t always been the best at CrossFit. He came second on his Games debut in 2014 to the legendary Rich Froning, whose four consecutive wins Fraser will likely equal this year. Froning then retired from individual competition, but Fraser rested on his Rookie of the Year Award: he trained a lot, but cut corners elsewhere. He ate badly (including a pint of ice cream a night), slept inadequately and didn’t warm up or cool down enough.

The favourite to win the 2015 Games, he blew a 100-point lead and came second again, this time to Ben Smith. Being the Second Fittest Man on Earth two years in a row is nothing to be ashamed of, but Fraser wasn’t proud of the effort he’d put in. He’d lost first, not won second. He hated his silver medals.

Fraser went away, licked his wounds and regrouped. He sought the help of top endurance coach Chris Hinshaw. He bought a Pig, the aptly named 254kg block of concrete-filled rubber that had contributed to his downfall at the 2015 Games, where athletes were required to flip it for 30m before four legless rope climbs and a 30m handstand walk. He practised late every Sunday. He sorted out his diet and recovery.

At the 2016 Games, Fraser, no gazelle, produced a shock by winning the opening 7km trail run, then came second in the “Suicide Sprint” shuttle run and the 85m handstand walk. It was the most dominant display seen at the Games – until his next one, and the one after.

The only thing more habitual than his wins is his daily routine. Two minutes after waking from a “minimum nine hours” of sleep, he eats breakfast, prepared by his fiancée, Sammy Moniz, who posts their hearty meals on the Instagram account @feedingthefrasers. Fraser doesn’t count macros. He has what he calls “100 points of energy” to spend every day. “I want to use as many of those points on training as possible,” he says. “If I’m worried about what I’m eating, that’s gonna cost me 20 points.”

After making a to-do list, Fraser trains at Froning’s box CrossFit Mayhem in Cookeville, Tennessee, where he and Sammy relocated in 2017. He eats lunch and runs errands, then trains for another two to three hours in his garage, working on his weaknesses. Then, he eats dinner, puts on Netflix while he stretches and foam-rolls for an hour before bed. He spends 99% of his days like this: “I’m a very happy individual.”

“Hard work pays off” is Fraser’s motto. The frequently hashtagged initialism #HWPO appeared on the tongue and insole of the Metcon 4 Mat Fraser, a “player-exclusive” version of Nike’s popular cross-training shoe that sold out almost immediately when it was released in May 2018. The two rings on the heel celebrated his victories up to that point. The knurled-look upper was inspired by a barbell. The leather back, quilted lining and gunmetal details nodded to his beloved motorbikes. The bull on the tongue represented the figurative steers in life that had bucked him – and driven him on. Fraser is a jewel in Nike’s crown and a coup in its rivalry with CrossFit’s partner Reebok. A ban on non-Reebok footwear at the Games has been lifted this year, but competitors still have to wear Reebok apparel.

He arrived at Nike’s Oregon HQ in May to be greeted by a giant banner of himself, which he called “an honour” – one that the brand says is reserved for “the world’s most venerated athletes”. It was also “pretty bananas” to get a Mat Fraser version of the Metcon. “When I give my parents a pair and my dad is, like, ‘OMG, you have your name on a Nike shoe,’ it’s just a sense of pride that you’re doing something right. It’s rewarding.”

Strong Background

His mum and dad were Olympians – not weightlifters but figure skaters, who competed as a freestyle pair at the 1976 Winter Games in Innsbruck, Austria. By the time Mat and his elder brother came along, his mother had graduated medical school to begin a career as a doctor, so his father gave up his real estate job to become a stay-at-home dad. Much of

the family’s fun was athletic. The four of them would move the coffee table to one side and hold handstand competitions in the living room. His father, who could handstand-walk down a flight of stairs, would bet Fraser a dollar that he couldn’t backflip on the trampoline, or jump from the roof onto the trampoline, then into the pool.

His mother, who clocked long hours, then spent all Saturday doing paperwork, made him do his homework when he got in from school. He was mystified when other kids couldn’t come out to play on Sunday because they still had to do theirs. Why hadn’t they done it on Friday? You had to do what you needed to before you could do what you wanted to.

Fraser played “a little bit of everything” at school, including American football, just so he could hang out with friends – he’d never seen a game and didn’t know the rules. He started weightlifting with similar ignorance at 12, competing with a friend to see who could hoist the most poundage overhead – “super unsafe” – when one of the coaches intervened. He soon learned that technique had to come before adding weight, even if it meant losing to other kids his age in the short term. Sure enough, years down the line, when his body developed, that hard work paid off, just as his coach had promised.

Diligent in training, Fraser was less disciplined outside the gym, staying up late to talk to girls on AOL’s instant messenger. He and his friends started experimenting with drink and drugs at the age of 10. He was hungover three out of four training days and thought it was normal to booze until he blacked out.

He was encouraged by his father to hang out with a man who was 10 years older than him. Fraser noticed that his new acquaintance was sober, as were all his friends. At a meeting where his mentor spoke about overcoming addiction, Fraser cried at the realisation that he, too, was an alcoholic. Still, it took a couple of years and the offer of a scholarship to the US Olympic Training Centre in Colorado before he went cold turkey.

A month later, when a friend asked him how he was doing in the gym, he broke down. His friend’s friend, who was also sober, volunteered to be Fraser’s sponsor and gave him Alcoholics Anonymous homework. The sponsor got in touch a few months ago. He’d taken up CrossFit and twigged that the Mat Fraser everyone was talking about was the 17-year-old he had supported.

Alcohol wasn’t the only bull that bucked Fraser. At 19, he broke his L5 vertebrae in two places during a lift. He was told that his sporting career was over. Four months of wearing a turtle-shell torso brace that pinched when he sat, driving him to try to rip off his steering wheel in frustration, did nothing. He rejected the recommended spinal fusion surgery for a more experimental treatment with a 50-50 chance of recovery, which involved re-breaking his back, power tools and two metal plates. Determined to lift again, he underwent a year of rehab at the Olympic Education Centre in Michigan, where he studied maths and physics with a view to a mechanical engineering degree, during which time his roommate had to lift him out of bed.

Burned out from weightlifting after a year back, Fraser briefly worked in an oil camp in Canada, then went to the University of Vermont to get his degree, loosely planning to land a job on an offshore rig. Instead, he wound up at an aerospace company that made actuators for missiles – not a bad gig, but he was miserable. “I went from training twice a day for 10 years to nothing and working 90 hours a week,” he recalls. “I was losing fitness, and it felt like I had a hole in my life.” He looked up a CrossFit box in Vermont, figuring it’d have better gear than a “Globo Gym”. He didn’t even know what a muscle-up was. But as he improved and was encouraged to enter competitions, he started to win $100 here, $500 there, in his inappropriate Nike Air Max 90s. His “part-time job” became a full-time occupation.

Truth be told, Fraser’s move to Cookeville was partly prompted by the nine reasons his new accountant gave him: Vermont levies 9% income tax, Cookeville none. But the city of 33,000 has become the CrossFit universe’s centre, with Froning the gravitational pull. Fraser often trains at Mayhem with Tia-Clair Toomey, the similarly dominant female champion who relocated from Australia, and her coach/husband, Shane Orr. Surrounding yourself with the right people who exert a positive influence is crucial for Fraser.

Even though he has fainted when giving presentations, Fraser has been dabbling in public speaking and was invited to tour with the United Service Organisation to boost the morale of American troops stationed overseas.

CrossFit is popular with the armed forces, if not all of the top brass, and Fraser’s most-asked question was how to turn a negative situation into a positive one. “I’m trying to inspire people to have a better work ethic, or chase whatever they want to chase,” he says. For that, there can’t be too many fitter.

This article originally appeared on Men’s Health UK.